Dave Bartholomew (ft. Tommy Ridgley): “Tra-La-La”

13 Sunday Mar 2022

Written by Sampson

Tags

No tags :(

Share it

DECCA 48216; JUNE 1951

History has a way of condensing narratives over time, of narrowing the focus of a complex story down to a singular theme that’s easy to remember even if it’s not quite accurate.

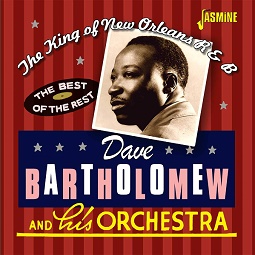

In the Cliff Notes version of the Dave Bartholomew story his career focuses on his extended stretch with Imperial Records, primarily as a producer, arranger and songwriter with occasional mentions of his concurrent recording career that resulted in a few memorable songs.

A slightly deeper overview – by that I mean an extra paragraph at best – will mention his earlier stint on DeLuxe Records where he scored one national hit as an artist, but beyond that you don’t get much more than basic biographical information.

The true story however, as always, is much more interesting and it’s here where we get the conflict that makes all good stories come to life… call this the start of the wilderness years.

Or better yet, taking a stand to prove a point.

Going Away To Stay

Over the past month we’ve covered two records by big name artists – Fats Domino and Smiley Lewis – where Dave Bartholomew’s decision in early 1951 to leave Imperial Records factored heavily into the product we heard from those other names.

We’d have liked to have covered Bartholomew’s side of the story first but it took awhile for him to cut his first – and only – session for Decca Records after his abrupt departure from Imperial which came about when Lew Chudd, the label owner, thoughtlessly gave a cash bonus to a local record store owner named Al Young, an overbearing white man who had the audacity to act as if the label’s success in the Crescent City was due largely to his guiding hand, despite the fact he did nothing other than act as a go-between for Chudd and the local talent when Imperial first came to town.

Bartholomew was the one responsible for everything that Imperial did in New Orleans. He recruited the singers, he put together the band, co-wrote and arranged the songs, produced the records and often played trumpet on them as well. Then, as if that wasn’t enough, he led the band in live appearances to promote the records.

In January 1951 he returned to the city after a grueling tour in which they got stiffed on the road by an unscrupulous promoter and was met by a gloating Young who waved the bonus check in his face. Bartholomew was incensed. He had gotten nothing other than the terms of his contract, while Young, who did nothing other than blow his own horn to an easily deceived Chudd, now was getting more money and with it more credit as well.

Bartholomew rightly quit.

We’ve told you that already, but here’s where Bartholomew landed as a result, Decca Records, where with Tra-La-La he sets out to make them pay for their ignorance. Featuring Tommy Ridgley, one of his first production credits for Imperial way back in late 1949 who handles the vocals here, he winds up getting a huge local hit in New Orleans, as the record rocketed up the local charts, landing at #2 before The Griffin Brothers cut a hasty cover and – due to their bigger name with the general public at this point – got more national attention for the song.

But even so its success served as a pretty big Fuck You to Imperial, showing he could cut hits with one of their castoffs, even if it also showed that Dave Bartholomew may have been hedging his bets just a little in the process.

City Bound

The choice to bring Tommy Ridgley along with him to Decca was both magnanimous of Bartholomew, who always had have a soft spot for those he’d known and worked with in the past, but also cagey in that he needed a more comfortable singer than Dave himself was to better his chances of breaking through.

Ridgley though was not without his drawbacks in this area, for he’s a very strident vocalist and prone to over-emoting, so with that in mind – as well as looking for a reliable formula to place his bets on – Bartholomew re-worked one of his first major hits as a producer in coming up with Tra-La-La.

The introduction in particular makes this connection to The Fat Man perfectly obvious, albeit without the infectious joy and barreling rhythm Fats Domino’s hit had to its credit. But it’s not straight rip-off either nor is it without its charms for while Ridgley’s vocal approach obliterates a lot of the nuance of the lyrics, his in your face style also serves to set off the subtleties of the arrangement behind him which is drastically toned down from its source material and shows Bartholomew’s evolving talents.

It’s almost as if this is a record with two aims, the first is to let Ridgley have his moment in the sun, but the second is to showcase the band’s skill which is directly attributable to Bartholomew’s guiding hand. This is the first iteration of his classic New Orleans studio aces and each of them plays a role in this gelling so well, from Salvadore Doucette’s dexterous piano opening to Bartholomew’s own trumpet flourish that follows it up. Then for the meat of the song the horn section as a whole contributes a lazy riff while Doucette is wriggling the keyboards beside Earl Palmer’s rock steady drums giving this a nice platform to build from.

Where it really stands out though is Clarence Hall’s tenor solo, a slow, sultry, grinding riff that proves you don’t always have to press the throttle to capture your attention. Here he never takes the instrument out of the slow lane yet you’re transfixed by every note. Then, as if that’s not enough, Bartholomew tosses in a transition to die for after the next vocal refrain courtesy of Ernest McLean’s guitar, something so discreet you might miss it but once you notice that distinctive ringing tone you’ll listen intently for it each time through.

There’s an alternate version they tried where Bartholomew’s trumpet is much more prominent, answering every line in a discreet fashion and sounds good – with a slightly more subdued vocal by Ridgley – even though it eliminates the great guitar part on the released (and slightly better) master.

‘Til You Come Back Home

In situations like this concerning a very public divorces, speculation is only natural and so you have to wonder what Bartholomew was thinking on this session.

Clearly he wanted to come up with a hit to stick it to Imperial and prove his value, which undoubtedly is why he chose to rework one of his biggest successes to date. Ridgley may not have been the best choice to carry it out but Bartholomew knew him well enough to realize his limitations and work around them on Tra-La-La.

But there’s another possibility that can’t help but creep into his thinking at this time. As proud as he was there had be part of him that was convinced that Imperial would beg him to come back. That might’ve even been why he signed with Decca – a major label – and yet only agreed to one session with a vocalist in tow.

In other words he wanted show his worth to Imperial with this move yet not tie himself down long term in the process, not use up his best original material and leave the door open to be wooed to come back. That could also be why he chose the B-side to this to indulge in his love of jazz with the classier Teejim, a style Decca was sure to appreciate more than an independent label used to rock ‘n’ roll.

But when no overtures were forthcoming from his old employers, even after the success of this single, Bartholomew realized he’d have to go his own way… maybe for good.

It’d be two years before things were smoothed over and he’d return to Imperial, but this record proved that he’d be just fine without them… maybe in some ways better than they’d be without him.

SPONTANEOUS LUNACY VERDICT:

(Visit the Artist pages of Dave Bartholomew and Tommy Ridgley for the complete archive of their respective records reviewed to date)

Spontaneous Lunacy has reviewed other versions of this song you may be interested in:

The Griffin Brothers (ft. Tommy Brown) (June, 1951)