Paul Williams: “Cranberries”

06 Monday May 2019

Written by Sampson

SAVOY 721; DECEMBER 1949

A-side, B-side… who the hell cares, right?

You couldn’t buy one without getting the other back then and it’s doubtful that many doing so really took the time to notice the label number and the little A or B next to that number when deciding which to listen to first. You’d play them both, decide which you liked best and go from there.

Eventually the music industry did away with the A-side/B-side dilemma by eliminating physical singles altogether, which of course also deprived the consumer of the two-for-one deal and the possibility that the song that hadn’t been thought of as highly by the label would in fact be the one listeners liked best.

But why all this talk about A-sides and B-sides here today? We generally cover both sides of singles here and we rarely pay much mind as to which is which, often choosing to write first about the B-sides simply because the story reads better that way.

This song however was in fact the A-side, which on the surface makes today’s intro seem rather pointless. But actually this is a case where there was some genuine internal debate as to which song should get the “honor” of the first write up when covering Savoy 721 because of the circumstances of the recordings themselves and the group cutting them.

Aye To Bee

Paul Williams was in a period of transition as the 1940’s drew to a close. The most prolific artist in terms of total number of releases – if you count his work on Wild Bill Moore’s records – Williams had been the first artist to release a rock instrumental back in October 1947 and then the first to score a national hit with another instrumental a few months later. A year after that he’d notched the biggest hit in rock to date when The Hucklebuck topped the charts for fourteen weeks earlier this year.

But along the way the band he started out with, the one which backed him on all of those hits, have been scattered to the wind in recent months. Moore had been cutting records of his own concurrently – the same band, the same sessions even, the only thing that changed was the focus from Williams’s baritone sax to Moore’s tenor – but when those records began to hit Moore moved on, put together his own group and left the Savoy label altogether.

Pianist T. J. Fowler has done the same, albeit without the benefit of a hit, as he’d gotten releases under his own name too with Williams and company behind him, including a tremendous song in Red Hot Blues and it didn’t take long for Fowler to depart as well.

Williams soldiered on, keeping his exemplary rhythm section of bassist Herman Hopkins and drummer Reetham Mallett together for a bit longer, but now they too have left his employ. The only familiar face left in the band is trumpeter Phil Guilbeau who himself had replaced original trumpeter John Lawton in the fall of 1947. The last few sessions Williams led he probably had to hand out name tags just to remember who the other musicians were.

But now we’re about to enter a period of relative stability when it comes to who’s backing Paul Williams. Not that this crew will remain together long themselves, in fact they’ll cut just two sessions with Williams before they’re gone as well, but the difference is their output during those sessions will make up the majority of Williams’s releases for the next full year and so there should be some semblance of consistency from one side to the next.

The reason we bring all this up and tie it in with the A-side and B-side of this release though is because the B-side, Juice Bug Boogie, which we’ll cover tomorrow, was actually recorded first, a month earlier in November 1949, the first time these musicians assembled in a studio as a unit. But while noting their arrival on that side might make better sense chronologically when it comes to making introductions, the fact is this where they assertively announce their arrival, on Cranberries, which perhaps is why Savoy chose this one as the A-side, chronology be damned.

Juiced

Nobody listening to the two sides in December 1949 would have known about any of this stuff, nor would they have cared – the same probably goes for many of you today in fact – but I’m guessing everybody WOULD care about the skill and compatibility of the accompanists when it comes to determining how good of a record they wind up delivering.

As this kicks off you’re kind of skeptical, especially considering the occasional lack of grit and urgency some of Paul Williams’s lesser efforts have featured to date, something this seems destined to join if things don’t pick up. There’s a simple walking stand-alone piano figure played by Lee Anderson that is familiar without it being particularly invigorating and it’s promptly joined by moaning horns that aren’t exactly out of date, but nor are they cutting edge in their delivery.

It’s a “safe sound” you think to yourself, not too daring yet not quite boring either.

A lot like Cranberries themselves in the fruit world come to think of it. They’re nothing that’s going to be devoured by those who crave the sweetness and juiciness of an orange or pineapple, but they’re also not more of an acquired taste like say mangoes or olives (yeah, they’re a fruit too… who knew?). Cranberries are just sort of there. Raw they’re nothing to rave about but with some work – sweetening, drying, juicing or baked into something – they’re pretty versatile, but I can’t imagine anyone picking it as an absolute favorite in the fruit world.

That would seem to be the case with the song these guys are building here as well. The slow, monotonous intro is suitably trance-inducing but hardly exciting… probably not destined to be somebody’s favorite Paul Williams track, though you never know.

When Williams makes his appearance however it’s a little startling. He’s playing very low in the baritone’s range and so his melodic options are rather limited. There’s a few times where he seems on the verge of slipping out of key momentarily and you wonder if they’re going to give over the entire song to showcasing him playing what essentially is a counterpoint to the recurring riff. When the other horns drop out and he gets a solo it’s interesting I suppose – I’d say unusual, since you don’t get many elongated baritone solos, but it’s played well so “unusual” is hardly the right word for it – but regardless of how captivating it might be to hear at first there’s really nowhere he can take it. As such the record is pleasant sounding but non-essential.

Until we meet the REST of the band that is.

Blow Freddy Jackson!

The loss of Wild Bill Moore a year earlier was tough for Paul Williams to overcome. It’s not that Moore was always raring to honk and squeal up a storm but when called upon to do so he was pretty damn good at it and at his best his scorching tenor playing against Williams’s resonant baritone could create major sparks. But truth be told Moore was someone who’d gotten his start in the years just before rock reared its gloriously ugly head and so he sometimes had to be urged to act up by producer Teddy Reig otherwise he’d often settle back into something a lot more placid and inconsequential.

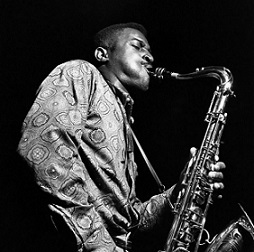

Newcomer Freddy Jackson seemed to have no such problems. For starters there’s his age, he had just turned twenty years old and as we’ve seen – and will continue to see until the present day – it’s the kids who will lead the way with each generation of rock. Unlike the their older brethren who cling to the standards of the past when it comes to how they should comport themselves on their instruments, the younger generation is determined to break those old rules and establish new ones of their own making. Nobody had to TELL Freddie Jackson to go crazy on the tenor sax, he was itching to do just that on his own.

Though somewhat a forgotten man in the lore of sax players of rock’s first decade, Jackson had a long and fruitful career after his brief stint here with Williams, as he played in Little Richard’s band before Richard hit it big and later led Lloyd Price’s outfit when Price was at his commercial peak. But it was with Chuck Willis in the early to mid-1950’s where he did his best work as Willis relied on Jackson’s ability to lay down romping beats to give Chuck the platform to launch his uptempo songs into orbit.

On Cranberries Jackson is the star from the second he makes his presence known at the midway point, taking over for Williams’s baritone and shifting the horn solo into a different, much more exuberant, plane. He kicks it off with a stuttering refrain that the other horns join in on before Jackson breaks free and starts to show off his melodic ability with a rich lusty tone, finally giving the song some structure to get into. Then it’s off to the races again with another stuttering lead-in to some soaring lines that hint at the famed Night Train riff that would emerge a few years down the road with Jimmy Forrest, all of which has you wondering where this might’ve headed had Jackson gotten a full song to cut loose on.

Sadly just as you’re getting really into it the record winds down. You have a notion to check the track to see if something got edited out – it’s only two minutes after all – but no, they definitely were wrapping it up in a pretty standard fashion so it’s not as if it doesn’t sound right, it’s just that you feel shortchanged in the bargain.

As a result you’re left wanting more and the reason for this is plain as day: we want to hear the newcomer blow some more. Though technically it may be Williams’s record, it’s clearly Freddy Jackson’s show.

Canning It

I suppose it’s a little unfair to say of the man who essentially made the saxophone into the dominant instrument of rock’s first decade that he wasn’t cut out for the position. Not that Williams himself wasn’t a really good player, or even that his instincts might’ve been slightly less adventurish than we’d like to see at times. No, those aren’t the reasons for his odd fit in the role of rock sax kingpin… it’s simply the fact that he played a baritone sax which by nature was more suited to be a supporting player to a more versatile and robust tenor.

Paul’s two best sides, The Twister under his own name, and We’re Gonna Rock under Moore’s aegis, saw that formula work to its best advantage, his baritone providing the necessary weight for Moore’s frantic tenor in both cases, but without a strong foil to play off of in the arrangements Williams struggled at times to find the right formula as the uptempo blasts that were still the most exciting rock records were all but removed from the mix.

But here in Freddy Jackson he’s got someone to go to war with. A tenor that not only CAN provide the necessary fire, but is itching to be a pyromaniac if given half a chance.

Unfortunately on Cranberries he IS only given half a chance, as in half the record, to strut his stuff, but the half he appears on gives every indication that he’s the real deal. The rest of the record is pretty good in its own right even if it might seem to be lacking in comparison to the climactic scenes Jackson delivers.

But instead of sloughing off Williams as some sort of an underachiever unless he’s got a top notch cohort with him maybe we should remind everyone that this is essentially the third time he’s overhauled his band and he’s notched plenty of good sides with all of them. The only constant in those lineups was Paul Williams which tells you that as a bandleader and a vital piece of the musical arrangements themselves he must be doing a “berry” good job.

SPONTANEOUS LUNACY VERDICT:

(Visit the Artist page of Paul Williams for the complete archive of his records reviewed to date)