The Four Blues: “It Takes A Long Tall Brown Skin Gal”

14 Sunday May 2017

Written by Sampson

Tags

No tags :(

Share it

APOLLO 398; APRIL, 1948

No lengthy preamble today, for the story of a group we’ll be meeting just this one time is hefty enough as it is without me rambling on in circles before we get to the review. If we exhaustively touch upon every moment of their careers you may have to call in sick for work or skip school tomorrow just to stick around until the end, so a cliff notes version will have to suffice in their case.

For Twenty Years, Mama, You Passed Me By

The Four Blues were around for quite awhile before rock ‘n’ roll came into being, their careers starting individually with other outfits back in the early to mid-1930’s in fact. By the dawn of the 40’s they’d joined up and formed The Four Blues and soon after signed with Decca, a major label indicating that they were seen as potential crossover artists, likely either in a pure pop vein or presented as some sort of quasi-novelty act, which was largely how black artists who were not blues, gospel or jazz acts were pigeonholed at the time.

On one hand it would appear they might be even aiming for the latter, as write-ups of their shows at the time seem to indicate they specialized in jive, the nonsensical fast-patter style popularized by Cab Calloway that was essentially blacks putting-on whites by use of exaggerated stereotypical characteristics for laughs, while whites naturally felt it was truly authentic and that thus it vindicated their deep-seated prejudices without it seeming nasty. But the sides The Four Blues laid down in the studio were much more in the pop vein – a little looser than white acts of the time for sure, but still pretty straightforward harmonizing on somewhat bland material. Decca wasn’t impressed apparently and held off releasing the material for two years, then when they did put it out the records sank without a trace.

The group essentially settled into being a club act after that, which isn’t quite the backhanded compliment it might seem to be today. The forties were an era when nightclubs still commanded a good deal of the entertainment dollar, much more so than records actually, and if you could establish your act as dependable, versatile and professional you could sustain a viable career for years without any records, as The Four Blues managed to do. But they were still known enough to get a few local blurbs in the black press drumming up business for their appearances when they came through town and along the way stirred up enough interest to entice DeLuxe Records to take a shot with them on wax in 1945.

It Ain’t No Use, My Preachin’ Days Have Passed

At this second stop too though their initial released sides for them were pretty much standard pop stuff, nothing special, and another opportunity seemed to be slipping through their fingers, either done in by conservatism or simply a lack of any real creativity. Maybe they WERE just a club act in the end – definitely a backhanded compliment now, in case you were wondering – a group that could deliver reasonably well on the bandstand when patrons used their music merely as a backdrop to their dining, drinking and conversation. If, after the meal and requisite socializing, they wanted to dance, well, The Four Blues music was effective enough for that I suppose. All in all though it seemed as if the group just was too tepid to break through.

But their follow-up on DeLuxe finally showed the group wasn’t going to fade into oblivion without at least putting up a fight. Baby, I Need A Lot Of Everything was definitely starting to look forward a bit. A song with a bluesy structure sung with decent rhythmic bounce as they contributed some pretty adventurish instrumental backing, particularly the guitar. If the bland straightforward ballads delivered by a thousand and one groups, both on record and in the clubs wasn’t enough to get you noticed, well, better to take a chance on something more invigorating and fall flat on your face than to simply waltz off demurely into the night unnoticed.

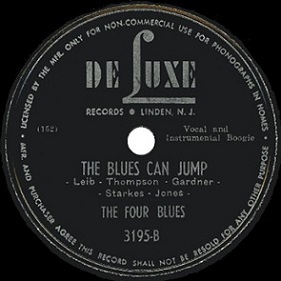

The unquestioned highlight of this period came with their fourth DeLuxe release, The Blues Can Jump, a song that definitely shares some of its structure with rock down the road, including a fast stinging electric guitar solo that sounds as if Danny Cedrone, who’d define Bill Haley & The Comets early rock efforts with a similar approach in the 50’s, was taking careful notes.

Though the vocals are a little subdued for what the content calls for most of the time and they get more gimmicky by the end while the other instrumental solos, including a stand-up bass and trebly piano, are also much further removed from even early rock sides that would come along two years later, it’s rescued by the pounding intro and that guitar, plus a dash of enthusiasm at times, all of which foreshadows rock fairly well. As early harbingers go, this wasn’t half bad.

Naturally showing promise in a still unformed but definitely exciting field they then don’t record again for three years. Go figure!

By the time they resurface with Apollo Records in 1948 rock had not only been born but had begun to flourish commercially and they got another shot at the brass ring in a style they were only tangentially connected to. By this point they had to sense that this would be their last “best” chance at breaking into the big time. So knowing that it’s a bit odd that they chose It Takes A Long Tall Brown Skin Gal, a song written way back in the 1910’s to try and connect with a forward thinking youthful new audience.

On paper it’d seem to be a rather futile effort, singing a song that was popular a quarter century earlier (although Louis Prima had revived it in 1946, bringing it at least some modern familiarity) to succeed in a marketplace that was barely a few months old by this point.

This probably isn’t going to end well, don’tcha think?

Well, think again.

What’s Good For You Is Sure Good For Me Too

Though not a masterpiece by any means, and actually almost schizophrenic in approach at times, what works here works incredibly well, so much so that you crave hearing more of it, or at least isolating those parts to dissect and analyze for future forays into rock.

Even the theme (the intoxicating beauty of the aforementioned Long Tall Brown Skin Gal), which considering the lyrics were written closer to the 19th century than the 21st, is perfectly suited for the era, the audience and the attitude of both.

The 13 second instrumental intro alone is worth a paragraph to itself for the way the piano establishes the rhythm while the guitar (sounding a bit too slack to really provide a deep bite, yet playing the right notes at the right pace to remain effective if someone had simply given him a better axe to use) rides over top of it. The effect is thoroughly invigorating and considering what we’ve complained about with so much of early rock being tied to the past, this is decidedly modern sounding in its arrangement.

The vocals come in with enthusiasm and panache, the backing voices in particular urging on Earl Plummer’s lead with their exultations (Yes! Yes!) in what would become a typical sing-along chorus that rock thrived on for years. The pace is infectious, their spirit is too, and while there are some strange choices made that drag it down – the plinking piano in the first break for instance which makes it sound clunky rather than exhilarating – there’s always something else to compensate for it, in that particular case the steady, almost slamming backbeat employed throughout.

In essence most of what’s found here is entirely right in structure, yet frequently a bit off in execution. It’s almost as if they somehow got hold of the right plans but read them upside down or something. Most emblematic of this is the fact that the horn solo, something which will define the best rock songs for a decade and thus upon which a lot is riding, is given over to… a clarinet!

Really? A clarinet??? You gotta be kidding me!

Yet despite that seemingly insurmountable obstacle for being taken seriously by rock fans it really digs down trying to match in intensity what sax solos were already establishing as a necessary component to raise the roof on the best rock records and damn near succeeds at it. Somehow at its best it manages to sound like an alto sax, squealing up a storm.

What you desperately want to do upon hearing all this is hop in a time machine and just tell them to make a few minor changes – have a tenor sax rather than a clarinet play the same riff with the same gritty passion, have them switch the right hand single-note piano solo with a dual fisted solo that pounds the keys until they turn black and blue, switch guitar models to one with a better and tighter tone and have the lead vocalist deliver the end of each line with more emphasis to really push the urgency of it rather than seeming to pull back and go for a more laid back tongue-in-cheek effect.

Minor corrections all, but if carried out they would’ve turned this from a curious experiment into a trendsetting gem.

The Congregation Tried To Make Him Stay

In the end, for all of its promise its minor flaws fight with its strengths and pull at you from opposite directions. If you listen with a mindset that focuses on a record’s best attributes you’ll definitely see this as above average for its time. But if you’re the type who is the first to spot a cloud in the distance at a picnic and immediately expect rain you’ll be more frustrated with its shortcomings, especially knowing they were all easily avoidable.

Either way you went I couldn’t argue, since both views are entirely right. Though NOT average in the typical sense, the score it gets winds up being average merely due to compromise. The above average attributes are pulled down by the below average aspects, or if you prefer, the poorer choices are redeemed by the inspired ones. Whichever your view you’d have to agree the results are fascinating if nothing else and will have you anxiously awaiting their next move, seeing where they’d take things the next time out.

But sadly they – and we – won’t get another chance for a reassessment on future work. They released only two more records, just one each for the next two years, never again approaching this style and never making those simple changes that may just have wound up positioning them to help lead rock into the future.

So close and yet so far.

SPONTANEOUS LUNACY VERDICT:

(Visit the Artist page of The Four Blues for the complete archive of their records reviewed to date)